A.Vincent Master: A Pioneer !

Jun 14 2025

Aloysius Vincent (1928–2015): The Visionary Cinematographer and Filmmaker Who Redefined South Indian Cinema

Born on June 14, 1928, in Kozhikode, Kerala, Aloysius Vincent—affectionately known as Vincent Master—was a trailblazing cinematographer and filmmaker whose career spanned over five decades, leaving an indelible mark on Indian cinema. Renowned for his work in Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, and Hindi films, Vincent was a pioneer who elevated South Indian cinema from its theatrical roots to a sophisticated art form.

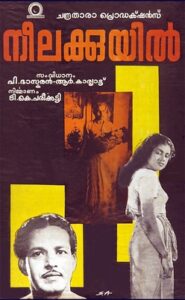

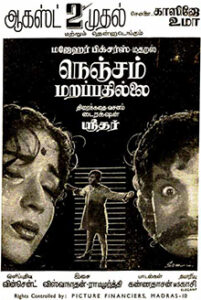

His innovative techniques, mastery of lighting, and bold artistic choices made him one of the most sought-after cinematographers of his era, with iconic films like Neelakuyil (1954), Amaradeepam (1956), Nenjam Marappathillai (1963), and Annamayya (1997) showcasing his genius. As a director, his debut Bhargavi Nilayam (1964) remains a landmark horror drama in Malayalam cinema.

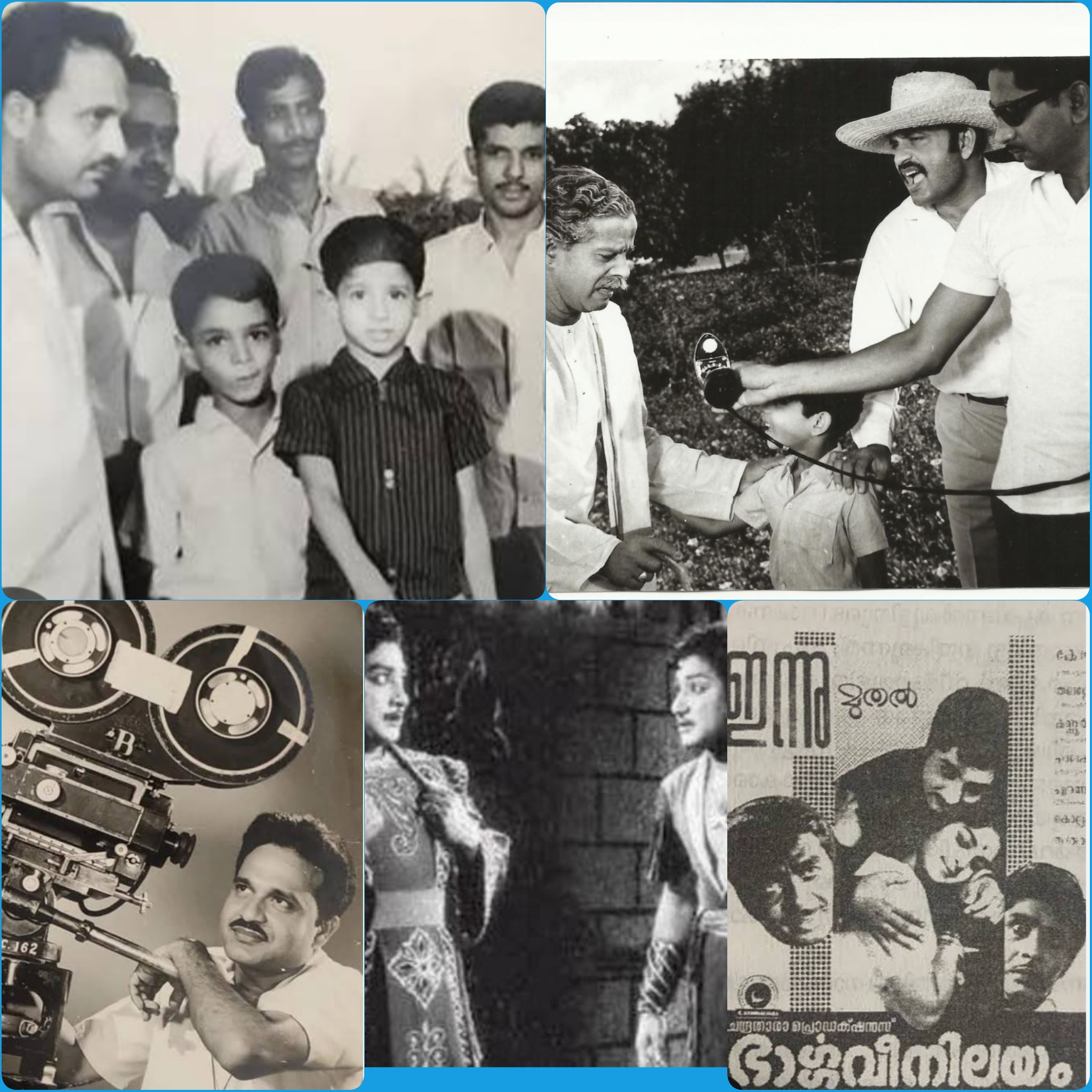

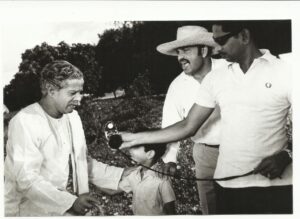

Vincent’s legacy continues through his sons, Jayanan and Ajayan Vincent, both accomplished cinematographers who have collectively lensed over 100 films.

Early Life and Introduction to Image-Making

Vincent’s fascination with visuals began in childhood, nurtured by his father, George Vincent, a teacher and photography enthusiast who ran Chithra Photo Studio in Kozhikode. Young Vincent spent countless hours in the darkroom, bathed in crimson glow, learning to develop film negatives—experiences that ignited a lifelong passion for image-making.

A Storied Career in Cinematography

Vincent began his cinematic journey in 1947 at Gemini Studios, Madras, as an assistant cinematographer. Working under luminaries like A. Natarajan and Kamal Ghosh, he contributed to landmark films such as Chandralekha (1948) and Apoorva Sagodharangal (1949).

In 1951, he moved to Bharani Studios, founded by P. Bhanumathi, and debuted as an independent cinematographer with Bratuku Theruvu (1953).

While contemporaries like Subrata Mitra (Pather Panchali, 1952) and V.K. Murthy (Jaal, 1952) were redefining Indian cinematography in their regions, Vincent carved his unique niche in South Indian cinema with his romantic ambiance and glamorous visuals.

His work on Neelakuyil (1954) introduced dynamic outdoor cinematography, using a bullock cart crane rig, a first in Malayalam cinema. Films like Gandharva Kshethram (1972) and Nizhalaattam (1970) showcased his flair for stylistic innovation, including Dutch angles, inverted framing, and what became known as the “Vincent School of Lighting”—a five-point setup that revolutionized black-and-white cinematography in South India.

Technical Ingenuity and Resourcefulness

In Uthama Puthiran (1958), he borrowed a 16mm Paillard Bolex camera from a French tourist to film a zoom sequence—a technique unavailable in India at the time. The footage was later blown up to 35mm at Kodak’s London lab, drawing international acclaim.

He also pioneered the “shadow mask” technique for dual-role scenes, allowing the same actor to move and interact within a single frame—a game-changer for Indian cinema.

Vincent as a Director

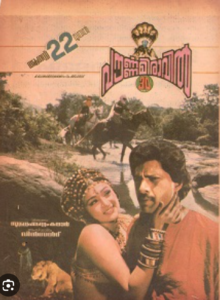

Vincent’s directorial debut, Bhargavi Nilayam (1964), remains a cult classic, blending supernatural themes with poetic romance. His later films like Murapennu (1965) and Thulabharam (1968) tackled bold socio-political themes, winning accolades including a National Award for Best Actress for Sharada.

At 60, Vincent embraced 3D cinema with Pournami Raavil (1985), and even stepped in for standby cinematography well into his senior years, stunning younger crews with his energy and expertise.

Collaborations and Industry Impact

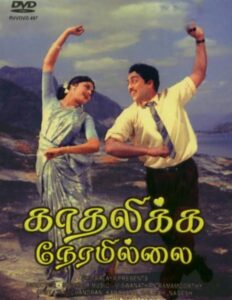

His partnership with C.V. Sridhar gave rise to Kalyana Parisu (1959), Kadhalikka Neramillai (1964)—Tamil’s first Eastman Colour film—and the successful Chitralaya banner.

He also worked on Jagadeka Veerudu Athiloka Sundari (1990), creating ethereal visual compositions with memorable songs like “Andalolo Aha Mahodayam.”

As the founding president of SICA (1972), Vincent was a champion of cinematographers’ rights. Known for his generosity in mentoring, he trained talents like P.N. Sundaram and Bhaskar Rao, often sketching frame compositions for their understanding.

Personal Traits and Legacy

Soft-spoken and intellectual, Vincent was a voracious reader, known for his perfectionism and willingness to take artistic risks. Actor Madhu praised his eye for detail, while his sons credit his encouragement and values for their own success.

He passed away in 2015, but his films, teachings, and lighting philosophy continue to shape Indian cinematography.

Trivia About Aloysius Vincent

- 🎥 First Outdoor Crane Shot: Neelakuyil (1954) used a bullock cart as a crane—first in Malayalam cinema.

- 🎭 Shadow Mask Pioneer: Seamless dual-role scenes in Uthama Puthiran (1958).

- 📸 Borrowed Camera Trick: Used a tourist’s 16mm Bolex camera for zoom effects.

- 🌈 Eastman Colour Breakthrough: Kadhalikka Neramillai (1964) was Tamil’s first in Eastman Colour.

- 🕶️ 3D at Sixty: Directed Pournami Raavil (1985), Malayalam’s second 3D film.

- 🛡️ SICA Founder: Established Southern India Cinematographers’ Association in 1972.

- 🎓 Mentorship Legend: Freely shared techniques with his peers and protégés.

- 👨👦 Legacy Carriers: Sons Jayanan and Ajayan Vincent continue his craft.

- 🌍 Pan-Indian Impact: Worked across four major film industries.

- 🏆 Award-Winning Direction: Thulabharam (1968) led Sharada to National Award glory.

- ✏️ Storyboard Sketches: Detailed artwork to simplify lighting setups.

- International Praise: Kodak London lab applauded his 16mm-to-35mm technique.

- 🎬 Chitralaya Co-Founder: With Sridhar, made enduring classics.

- 👻 Horror Pioneer: Bhargavi Nilayam (1964) paved the way for psychological horror in Malayalam.

- 💡 Lighting Legacy: “Vincent School of Lighting” still revered in film circles

Elaborated Trivia: The Shadow Mask Technique in Uthama Puthiran (1958)

One of Vincent’s most groundbreaking innovations, the “shadow mask” technique, transformed dual-role cinematography in Indian cinema. Unlike static matte shots of the time, this method allowed dynamic movement and realistic interaction between two characters played by the same actor.

Using precise lighting, Vincent would shoot the actor in one half of the frame, rewinding the film and repeating the process with reversed lighting for the second character. The result? A seamless scene where Sivaji Ganesan as twin brothers could walk past each other, talk, or even physically interact—a feat unimaginable at the time.

It was particularly impactful because Uthama Puthiran was based on The Man in the Iron Mask, and the narrative hinged on twin dynamics. Vincent’s solution not only solved a technical challenge but elevated storytelling, becoming a template for future dual-role scenes in Indian cinema.

Aloysius Vincent was more than a cinematographer or director—he was a visionary who blended technology, aesthetics, and humanity into his art. Through his films, teachings, and legacy, he remains an eternal flame in the heart of Indian cinema.

Drafted by

CJ Rajkumar

Author/ Cinematographer