Night Cinematography: Finding the light?

Oct 05 2025

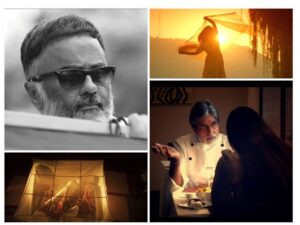

A Cinematographer’s Search for Light Through Darkness

There was a time when cinematography was defined by the math of light — by foot-candles, motivated sources, and carefully plotted beams. We chased realism by showing the audience where every light came from.

Masters like PC Sreeram paved new way of thinking, that light can originate and hit into the frame from anywhere…defines the edge of our art.

Today, the sensor has changed the language of light — and with it, the very philosophy of how we illuminate a story.

With earlier article which has a draft of fundamental approach, Award winner PC Sreeram in conversation with SICA shares his thoughts that…Light should be felt it can be surreal,magical or functional.

1. The Digital Sensor Has Changed the Rules

Modern cinema cameras see deeper into darkness than the human eye. With base ISOs of 800 to 2500, dual native ISO sensors, and dynamic ranges exceeding 15+ stops, they allow us to work at light levels that would have been impossible on film.

Where once we needed 10 to 20 foot-candles to register detail, today 2 or 3 fc can deliver a textured, cinematic image with extraordinary nuance.

This shift frees us from the tyranny of over-illumination. It allows us to explore the thinnest layers of light — faint reflections, accidental glints, or a soft trace of ambience — and still render them as emotionally rich images. Light no longer needs to overpower darkness; it can breathe within it.

🕯️ 2. Light as a Surprise, Not a Source

Pc Sreeram shares his thoughts

light at night should be a surprise — it should appear without explanation, woven into the mood rather than justified by a fixture.

“The audience should never search for the source of light. They should only feel its presence.”

This doesn’t mean abandoning discipline. It means freeing light from geography and allowing it to become part of the story’s soul. A shaft of light might emerge from an unseen distance, or a backlight might exist with no visible lamp — yet if the emotion is right, the viewer accepts it as truth.

In this way, light transforms from a physical presence into a psychological force.

🌌 3. Illumination Through Darkness

Perhaps Sreeram’s most radical idea is that darkness is not the absence of light — it’s the space where light is born. The cinematographer’s role is not just to add illumination, but to discover it hidden within the scene.

- A small reflection off wet cobblestones

- A distant sodium-vapor glow shaping a silhouette

- A faint sliver from an unseen doorway

- A glint from a metallic prop that becomes a fill source

In traditional thinking, these are “accidents.” In Sreeram’s approach, they are the intentional brushstrokes of visual poetry.

Technically, this is possible today because sensors maintain detail even at ISO 3200 or 6400 without unacceptable noise. A 1–2 fc trace on a dark surface — invisible on celluloid — can now anchor the mood of a scene.

🎨 4. Mood Over Motivation, Emotion Over Explanation

Traditional lighting often prioritizes logic: “Where is the light coming from?”

Sreeram urges us to prioritize emotion: “What is the light saying?”

By detaching illumination from explanation, the cinematographer becomes freer to design images that serve narrative tone over spatial realism. A character emerging from darkness can be gently kissed by a key that has no visible origin — yet if it expresses vulnerability or mystery, it has fulfilled its cinematic purpose.

This philosophy invites a shift in how we think of contrast. Instead of designing ratios on paper, we feel the tension between dark and light on set, adjusting exposure and intensity instinctively to shape emotion rather than data.

⚙️ 5. A New Kind of Discipline

This approach is not a rejection of craft — it’s a more subtle discipline.

It demands a deeper understanding of sensor behavior, noise floors, and highlight roll-off. It requires meticulous control over micro-sources — small LED accents, reflections, and indirect bounces — and an ability to shape the image without obvious fixtures.

It also asks us to rethink exposure tools. False color, waveform, and HDR monitoring allow us to place faint traces of light precisely where we want them — sculpting tone curves rather than chasing brightness levels.

The reward is profound: images that feel less “lit” and more felt, where darkness itself becomes part of the storytelling language.

✨ Tradition and Evolution: Two Languages of Light

The classic approach — with foot-candle targets, motivated sources, and diagrammed setups — remains essential. It gives us control, repeatability, and a shared language with our crew.

Modern approach — intuitive, poetic, mysterious — offers something different: an emotional grammar built from the interplay of darkness and suggestion.

In the hands of a mature cinematographer, these aren’t opposites. They are two languages of the same art — one rooted in precision, the other in feeling. Mastery lies in knowing when to speak which.

Drafted by

CJ Rajkumar