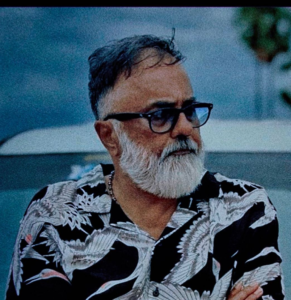

In Conversation: Mahesh Muthuswami

Oct 18 2024

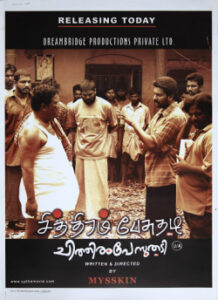

Mahesh Muthuswami is an acclaimed Indian cinematographer known for his dynamic visual storytelling and innovative use of light and camera movement. A graduate of the prestigious Pune Film Institute, Mahesh has worked on critically acclaimed films like Chithiram Pesuthadi, Anjathey, and Nandhalaala with directors like Mysskin, Pandiraj, and Radha Mohan. His signature style blends technical precision with artistic depth, making him one of the most respected DOPs in Indian cinema today.

In Conversation: Mahesh Muthuswami

Can you tell us about your first interest in cinematography and what drew you to this field?

My interest in cinematography began quite unintentionally during my college days at PSG College of Technology, Coimbatore. I was part of the photographic club there, mostly because my friend Muthuselvam was really good at photography. I used to assist him, do small tasks to support his passion, and in the process, I started learning. I never thought it would evolve into something I’d pursue seriously.

But one day, I watched Piravi, a Malayalam film shot by the brilliant Sunny Joseph, on Doordarshan. That film was a revelation for me. It was so different from the mainstream films I had seen in theaters; it felt deeper and more authentic. It showed me how cinematography could go beyond mere visuals and capture a raw, emotional essence. Around the same time, I had another powerful experience while watching Oomai Vizhigal. There’s this climax scene where the car marches forward, and the entire theater erupted in applause. That visual of cinematigrapher A Ramesh Kumar struck me—there was a kind of magic in it. It was at that moment that I realized the true power of visuals and decided I wanted to pursue cinematography as a career. Visuals could move people, change them. I wanted to be a part of that.

How did your time at Pune Film Institute shape your approach to cinematography?

The Pune Film Institute was life-changing in many ways. It’s not just about the technical training but also the exposure to different kinds of cinema and the people you meet. During my second year, I met a direction student named Kranti Kanade. There was something about his energy, his passion—it was intense. I knew right away that he was going to make a significant impact in the industry. We became close collaborators.

Our final diploma film, Chaitra, was a project that meant a lot to me. It was based on a story by the well-known Marathi writer G.A. Kulkarni. What made it even more special was that it was the first time the Pune Film Institute used cinemascope lenses, and I was fortunate enough to shoot with them. That film went on to win the National Film Award, was recognized at the Mumbai International Film Festival, and even became India’s student entry for the Oscars. It was a big moment for us—an affirmation that we were on the right path, creating meaningful cinema. The success of Chaitra taught me that with the right vision, you could transcend the limits of what’s expected, even as a student.

How did your collaboration with Mysskin on Chithiram Pesuthadi come about?

Mysskin is a director with a distinct style, and when I first met him, he was searching for a cinematographer with a strong showreel. Interestingly, what sparked our connection was a book I noticed on his table—In the Blink of an Eye by Walter Murch. That book is about editing, but it speaks to the language of cinema, and it instantly gave us common ground to build our creative relationship.

From the beginning, Mysskin had a clear vision for how he wanted his films to look and feel. He wasn’t just looking for someone to execute shots; he was looking for someone who could help him shape a new cinematic language. He had a unique rhythm when designing scenes, especially in how he conceived the first shot and let it dictate the flow of the others. As a DOP, I knew I had to allow that rhythm to emerge without interfering too much. I didn’t try to balance the frames just for aesthetic reasons, especially in wide shots. Instead, I let the light spill onto the walls naturally, creating an unpolished, raw look. It was about giving the film room to breathe and helping Mysskin’s vision come alive.

Anjathey is considered a major turning point in your career. What was the experience like working on that film?

Anjathey was an incredible experience and indeed a turning point in my career. Mysskin’s storytelling in Anjathey was different from Chithiram Pesuthadi. It was darker, more introspective, and I knew that the cinematography had to reflect those tones. The story revolves around two characters whose lives take completely opposite directions, and I wanted to symbolize that contrast in the visual design.

I focused a lot on subjective camera movements and compositions, trying to immerse the audience in the characters’ internal struggles. There’s a recurring theme of fear in the film, especially in the night sequences. To amplify that, I used minimal lighting with strong highlights to create tension and suspense. One shot that stands out is the long, low-angle trolley shot following the footsteps—it’s become iconic now, but it was entirely Mysskin’s idea. That’s the magic of our collaboration: he comes up with these powerful concepts, and I bring them to life visually

You and Mysskin collaborated again on Nandhalala, which had a different feel from your earlier films. How did you approach that project?

Nandhalala was an incredibly personal film for Mysskin because it drew heavily from his own family experiences. He played the central character, and that created a deeper emotional connection to the material. The film was inspired by a Japanese work, but we both wanted to distance ourselves from what we had done before.

This time, we used long telephoto lenses, which created narrow, intimate views. It gave the film a sense of isolation and focused attention on the characters’ emotions. The result was a series of bold, almost painterly images that captured the essence of the story in a way that felt raw and personal. It’s a film that holds a special place in my heart because of how much it meant to Mysskin and how different it was from our previous collaborations.

You’ve worked on a wide range of films. What was your approach to the visual style of Vamsam and Mouna Guru?

Vamsam was a fascinating project with Director Pandiraj. For that film, I wanted to focus on the texture of the visuals, and I chose to experiment with frontal lighting to bring out the textures in the environment and characters. It was a new direction for me, visually speaking, and it gave the film a distinct look.

For Mouna Guru, directed by Shanthakumar, I took a different approach. The film revolves around characters who undergo significant transformations, and I wanted the lighting to reflect that. I played with lighting setups that shifted throughout the film, creating a dynamic range of lighting levels that corresponded with the characters’ emotional arcs. It was all about using light to subtly enhance the storytelling.

Your work with Director Radha Mohan is well-regarded. What stands out to you about that collaboration?

Radha Mohan is a very special director to work with. His strength lies in his characters and the way he writes dialogue. He’s very precise when it comes to those elements, but when it comes to the visuals, he trusts me entirely to design the visual scheme. We worked on Uppu Karuvaadu and Kaatrin Mozhi together. Even though Kaatrin Mozhi was a remake, Radha Mohan wanted a fresh approach that matched his emotional storytelling style.

What I love about working with him is the freedom he gives me to interpret the script visually. It allows me to bring my own creativity to the table while staying true to the essence of his stories. It’s a rare kind of collaboration, and I cherish it.

You started your career as an assistant to P.C. Sreeram. What was that experience like?

Working with P.C. Sreeram was like a masterclass in itself. He is a legend, and learning under him shaped much of my approach to cinematography. During the days of film cameras, the eyepiece would often flicker intermittently, but we had to maintain complete control over the frame, even with that limitation. One day, during an ad shoot, he asked me to operate a shot. After it was done, he said, “Did you see the God?” That statement really resonated with me. As a cinematographer, when you’re looking through the viewfinder, you’re completely immersed in the moment. It’s almost a spiritual experience, where you lose yourself in the frame. That’s what he meant—between ‘action’ and ‘cut’, you’re in a different world, creating something magical.

As a cinematographer, do you have a particular preference when it comes to lenses?

Yes, I have a strong preference for prime lenses over zoom lenses. There’s something about prime lenses that makes the image feel more pure, more intentional. With primes, you’re forced to think about your frame more carefully—how close or how far you want to be from the subject, and how that affects the emotional impact of the scene. I find that primes give a sharper, more detailed image and allow for more control over depth of field, which can be a powerful storytelling tool.

My favorite lens is the 32mm prime. It’s the perfect middle ground for me. It’s wide enough to give context and environment but not so wide that it distorts the faces of the characters. The 32mm brings the audience into the world of the film without overwhelming them with too much information. I’ve used it extensively in many of my projects because it has a way of capturing both intimacy and space, making it versatile for a range of scenes—from character close-ups to wider environmental shots. To me, it’s a magical lens that strikes the right balance in framing the human experience.

You’ve recently worked on Genie, which is quite different from your previous projects. What can you tell us about it?

Genie is an exciting project for me. It’s a Jayam Ravi starrer directed by Arjunan Jr., and it has a strong visual design that challenged me to push my boundaries. The film has a fantasy element, which allowed me to explore new visual techniques, especially with CG. This is the most controlled use of CG in my career so far, and it was crucial that we didn’t let the technology overpower the narrative. We worked to strike a balance between the fantasy elements and the grounded emotional core of the film

Article by

CJ Rajkumar

Author/ Cinematographer